SANDU UVC

A LOW COST PPE decontamination Solution

This was an in-house studio project funded by the Netherlands Government and run by FROLIC Studio while I was working there.

My role: Design Research Lead, UX and Interaction Design

Team: Alexander Selg (Industrial and UX Designer), Ismael Velo Feijoo (Product Design Lead)

Design RESEARCH Challenge

During the pandemic in 2020, FROLIC Studio decided to channel its resources and network into finding ways to help overcome the critical challenges posed by COVID-19. After an initial open source prototype being generated based largely on European insights, a new, improved and low-cost version of the decontamination box was developed for healthcare workers in emerging markets, namely Uganda.

RESULT

A low cost, portable and adaptable decontamination device that is inclusive to different users and contexts. With a protocol integrated into the guiding them through the procedure for safe and efficient decontamination, it allows people to decontaminate their PPE efficiently, making it usable for longer when there are shortages.

INTRODUCING SANDU UVC

Sandu UVC is a low-cost decontamination device that disinfects PPE by removing all traces of different viruses and bacteria—including COVID-19—using the process of Ultra-Violet Germicidal Irradiation. By using the device, the lifecycles of PPE can be increased, saving on resources, particularly for healthcare facilities with budget constraints.

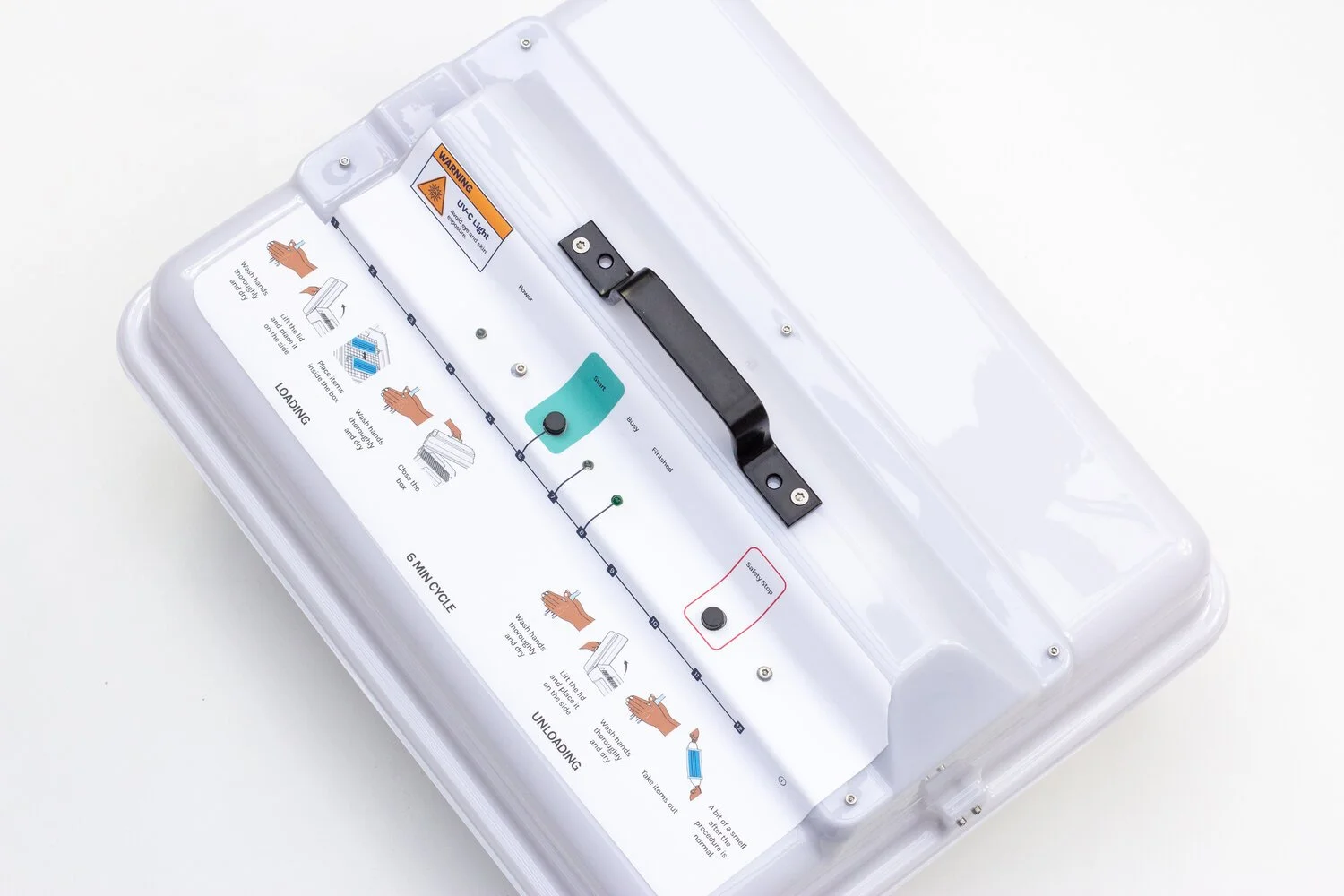

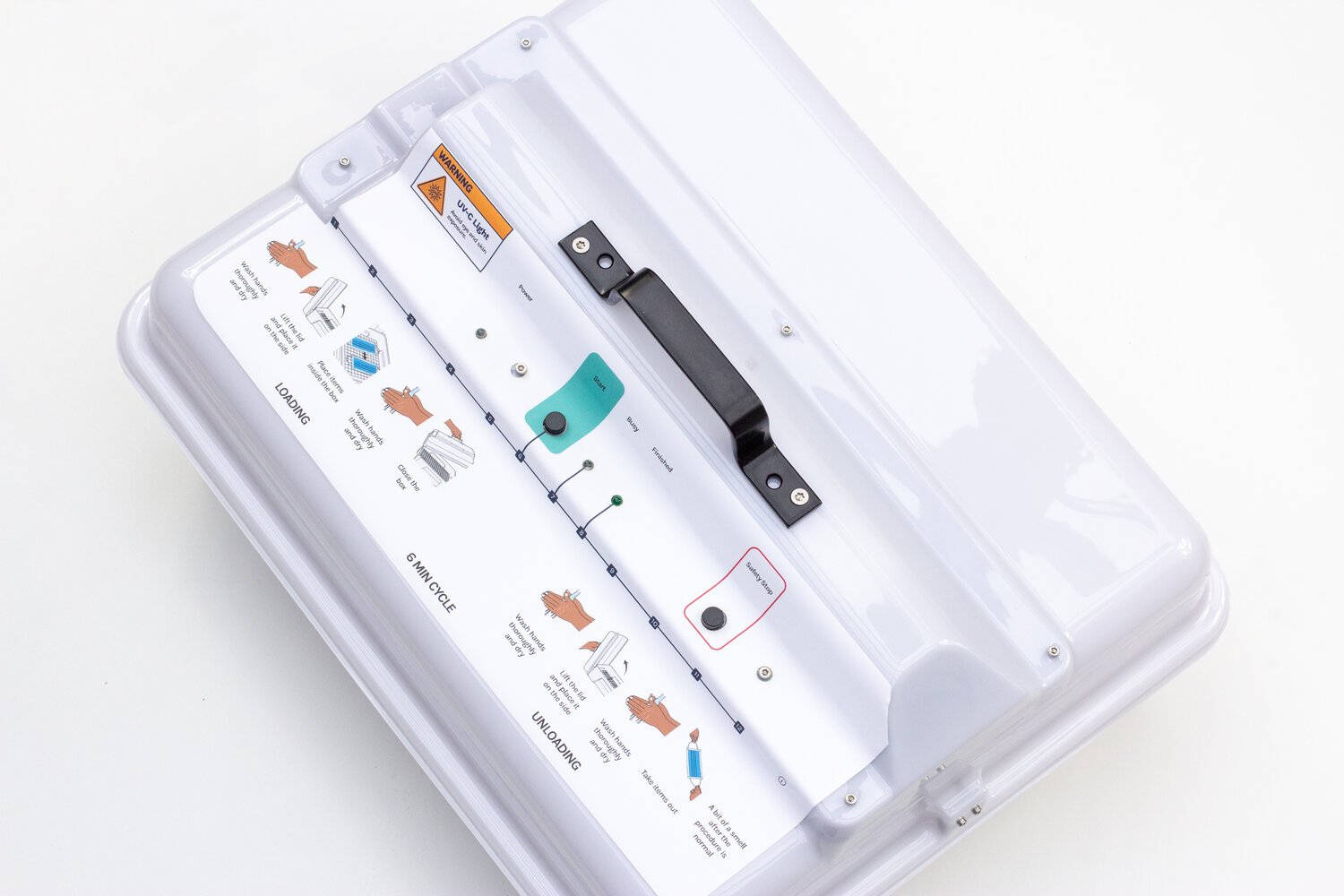

InCLUSIVE Interface

The Sandu UVC protocol is integrated into the interface using simple visuals, and takes users through the decontamination process, step by step, which make it easy and accessible to use for different users, ensuring safe and effective use.

The instructions are applied to the hardware is a simple sticker which can be changed cheaply and easily if needed.

HOW We GOT There…

Prioritising HUMAN NEEDS

We began with an in-depth analysis of different care facilities in Uganda, allowing us to explore the reality of health practitioners at ground level while keeping human-centred design principles as our main focus through out the process. The aim was to understand how COVID-19 affected these frontline professionals, how the use of protective equipment had changed, and what they needed in order to better contain the spread of the virus.

One way to get around restrictions of photography was to provide a drawing space on the response packs.

DEEPENING UNDERSTANDING Remotely

Because of lockdown restrictions, our initial challenge was to carry out research in Uganda remotely. On top of the limitation of the lockdown, we were initially working with healthcare institutions with strict limitations around taking videos and photographs and workers who had very limited time to give us.

To understand the environments we were designing for better, we asked people on the ground to sketch the layouts of the facilities so we could better understand the spacial context that people were referring to in interviews and surveys. In surveys and interviews we asked about how people felt about their work, how they experienced the environment so we could really design something that could fit easily into their lives and not add cognitive load.

ChAllENGING OUR ASSUMPTIONS ANd BIASES

During this project, I was accutely aware of my position as a European designer working in an African context of which I had very little knowledge. Before we started the research we reflected on our assumptions and made sure we had check ins through the process to see how these were being challenged. Some of our hidden assumptions that we acknowledged were:

English will be a universal language, understood by most people in Uganda.

Medical practises are roughly universal everywhere and therefore the conditions of work will be similar to Europe

There will be a need for the decontamination box as most institutions will be running out of disposable PPE and have no way to recycle it.

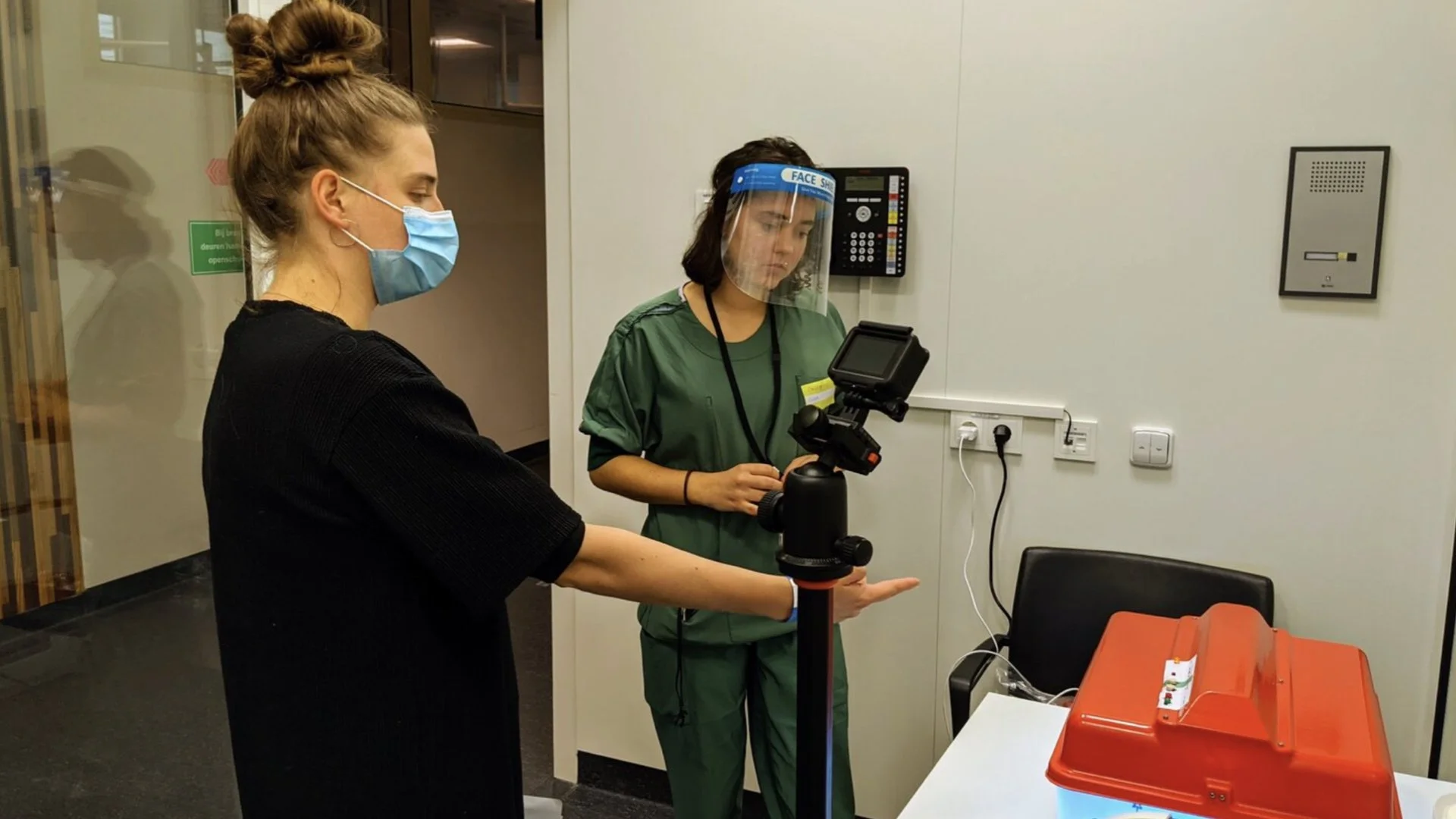

Usability testing in and Amsterdam Hospital during lockdown

ITERATIVE PROTOTYPING

While we were able to carry out some basic usability testing in the Netherlands, it was vital for us to collaborate with local research partners and clinics in Uganda for a first-hand understanding of the context and people were designing for. We wanted to ensure we challenged any assumptions in order to gain unbiased insights and guide our design decisions.

Once lockdown had eased, the team were able to get a pilot version of the box out to healthcare centres and carry out research with people on the ground. From identifying power demands to understanding the hygiene protocols, the research and design process was carried out with and for the Ugandan medical community.

The original open source version of the decontamination box.

Prototype ready for pilot following initial round of research

Insights

The main takeaways from our research were:

A general shortage of PPE means staff were already used to washing and recycling PPE as part of their internal systems.

Like most healthcare facilities, people are very busy, on their feet and have interrupted work flows throughout the day.

Different languages, levels of literacy and workflows call for an adaptable design that can be understood visually, accessible interface that can be understood without having to read English

There is competition for space in many healthcare institutions and things are often moved around to make space for whatever is needed.

InTEGRATING INSIGHTS

Inclusive interface

The Sandu UVC protocol is integrated into the interface using simple visuals, and takes users through the decontamination process, step by step, which make it easy and accessible to use for different users, ensuring safe and effective use.

The instructions are applied to the hardware is a simple sticker which can be changed cheaply and easily if needed.

Portablity

It became clear from the insights that having a device that could be easily stored and put away was key to it being successfully integrated into their work lives. It making decisions for the second interation, the team therefore aimed to make it lightweight as possible, with build in handles and a detachable cable.

VISIBLE

The box itself is translucent and glows when it is in the process of disinfecting making it easy to know when it is running and when it is finished, without having to check the interface up close. The catch in the lid means that not UV escapes from the device, making it safe to use in busy settings.